Ομολογώ: είμαι σταλεγάκιας. Όταν τα έλεγα εγώ, κάποιοι δεν κράταγαν σημειώσεις. Αλλά θα τους δείξω εγώ τώρα.

Στην υπόθεση Vinter και λοιποί κατά ΗΒ (Ιούλ 13), η Διηυρυμένη Σύνθεση του ΕΔΔΑ έκρινε ότι η επιβολή πραγματικής ισόβιας κάθειρξης, ήτοι ισόβιας κάθειρξης χωρίς υφ’ όρον απόλυση, παρά μόνο με την δυνατότητα χάριτος, παραβιάζει το άρ. 3 ΕΣΔΑ περί απάνθρωπης και εξευτελιστικής μεταχείρισης. Και μαλιστα με ψήφους 16-1, όπου ακόμη και ο Άγγλος δικαστής υπερψήφισε την διάγνωση της παραβίασης.

Εξυπακούεται ότι οι τρεις αιτούντες δεν είναι καλά παιδιά.

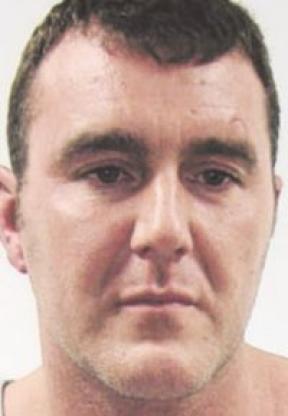

Ο Βίντερ, 44 ετών σήμερα, δεν είναι σοφός ανήρ. Το 1996 δολοφόνησε ένα συνάδελφό του σιδηροδρομικό με μαχαίρι. Έμεινε στην φυλακή 9 χρόνια (είπατε τίποτα για τιμωρητικότητα του συστήματος;). Όταν βγήκε, παντρεύτηκε, και, καλά το μαντέψατε, δολοφόνησε και την σύζυγό του το 2008. Την στραγγάλισε και την μαχαίρωσε. Το δις εξαμαρτείν είναι εκείνο που τού στοίχισε την καταδίκη σε πραγματική έκτιση ισοβίων.

Ο Μπάμπερ, 52 ετών, σκότωσε όλη του την οικογένεια, 5 άτομα εν όλω, το 1986, όταν ήταν 25. Ήταν υιοθετημένος και σκέφτηκε, φαίνεται, ότι αυτός θα ήταν ένας καλός τρόπος να κληρονομήση τους θετούς γονείς του. Λάθος.

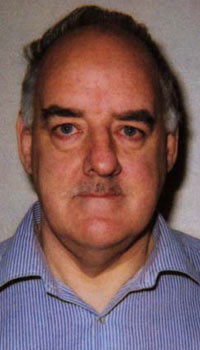

Ο Μουρ, 73 ετών σήμερα, δολοφόνησε τέσσερις άνδρες το 1995. Θύτης και θύματα ήταν όλοι ομοφυλόφιλοι, οι δε φόνοι τελέστηκαν σε άμεση συνάφεια με στέκια ομοφυλόφιλων. Ο Μουρ χρησιμοποιούσε ένα μαχαίρι εκστρατείας.

Τίποτε δεν κάνει τους καταδίκους αυτούς συμπαθείς. Για να είμαι ειλικρινής, θα προτιμούσα απλώς να μην ζούσαν (και να μην τους πληρώνουν κιόλας και οι Άγγλοι φορολογούμενοι).

Η απόφαση λοιπόν τα λέει όμορφα και μαζεμένα:

106. […] Contracting States must also remain free to impose life sentences on adult offenders for especially serious crimes such as murder: the imposition of such a sentence on an adult offender is not in itself prohibited by or incompatible with Article 3 or any other Article of the Convention. This is particularly so when such a sentence is not mandatory but is imposed by an independent judge after he or she has considered all of the mitigating and aggravating factors which are present in any given case.

107. However, the imposition of an irreducible life sentence on an adult may raise an issue under Article 3. There are two particular but related aspects of this principle that the Court considers necessary to emphasise and to reaffirm.

108. First, a life sentence does not become irreducible by the mere fact that in practice it may be served in full. No issue arises under Article 3 if a life sentence is de jure and de facto reducible.

In this respect, the Court would emphasise that no Article 3 issue could arise if, for instance, a life prisoner had the right under domestic law to be considered for release but was refused on the ground that he or she continued to pose a danger to society. This is because States have a duty under the Convention to take measures for the protection of the public from violent crime and the Convention does not prohibit States from subjecting a person convicted of a serious crime to an indeterminate sentence allowing for the offender’s continued detention where necessary for the protection of the public. Indeed, preventing a criminal from re-offending is one of the “essential functions” of a prison sentence. This is particularly so for those convicted of murder or other serious offences against the person. The mere fact that such prisoners may have already served a long period of imprisonment does not weaken the State’s positive obligation to protect the public; States may fulfil that obligation by continuing to detain such life sentenced prisoners for as long as they remain dangerous.

Στο χωρίο αυτό βέβαια το δικαστήριο μοιάζει να συγχέη ποινή με μέτρα ασφαλείας. Αν το ερμηνεύσουμε κατά γράμμα, θα ήταν επιτρεπτή η εγκάθειρξη ενός καταδίκου χωρίς να συντρέχουν λόγοι ανταπόδοσης, ειδικοπροληπτικοί ή γενικοπροληπτικοί, απλώς και μόνο επειδή εξακολουθεί να είναι επικίνδυνος. Η επικινδυνότητα του εγκληματία συμπροσδιορίζει βέβαια την ποινή κατά την επιμέτρησή της, αλλά δεν την στηρίζει αυτοτελώς.

109. Second, in determining whether a life sentence in a given case can be regarded as irreducible, the Court has sought to ascertain whether a life prisoner can be said to have any prospect of release. Where national law affords the possibility of review of a life sentence with a view to its commutation, remission, termination or the conditional release of the prisoner, this will be sufficient to satisfy Article 3.

110. There are a number of reasons why, for a life sentence to remain compatible with Article 3, there must be both a prospect of release and a possibility of review.

111. It is axiomatic that a prisoner cannot be detained unless there are legitimate penological grounds for that detention. As was recognised by the Court of Appeal in Bieber and the Chamber in its judgment in the present case, these grounds will include punishment, deterrence, public protection and rehabilitation. Many of these grounds will be present at the time when a life sentence is imposed. However, the balance between these justifications for detention is not necessarily static and may shift in the course of the sentence. What may be the primary justification for detention at the start of the sentence may not be so after a lengthy period into the service of the sentence. It is only by carrying out a review of the justification for continued detention at an appropriate point in the sentence that these factors or shifts can be properly evaluated.

Πολύ σωστά. Με απλά λόγια, ειδικά η ειδική πρόληψη ενδέχεται να επιβάλη την αποφυλάκιση του καταδίκου. Στο κάτω κάτω, ακόμη και ο Κοεμτζής δεν δολοφόνησε ξανά. Ποιο θα ήταν το κέρδος αν πέθαινε στην φυλακή δηλαδή;

112. Moreover, if such a prisoner is incarcerated without any prospect of release and without the possibility of having his life sentence reviewed, there is the risk that he can never atone for his offence: whatever the prisoner does in prison, however exceptional his progress towards rehabilitation, his punishment remains fixed and unreviewable. If anything, the punishment becomes greater with time: the longer the prisoner lives, the longer his sentence. Thus, even when a whole life sentence is condign punishment at the time of its imposition, with the passage of time it becomes – to paraphrase Lord Justice Laws in Wellington – a poor guarantee of just and proportionate punishment.

Το περί εξιλέωσης επιχείρημα δεν μου αρέσει, έχει θεολογικές αναφορές που με ενοχλούν. Στο κάτω κάτω, την ποινή αποφασίζει το δικαστήριο, όχι ο κατάδικος με την συμπεριφορά του. Η ουσία της επόμενης σκέψης φαίνεται να έγκηται στην δυσαναλογία εγκλήματος και ποινής και με βρίσκει μάλλον σύμφωνο.

113. Furthermore, as the German Federal Constitutional Court recognised in the Life Imprisonment case (see paragraph 69 above), it would be incompatible with the provision on human dignity in the Basic Law for the State forcefully to deprive a person of his freedom without at least providing him with the chance to someday regain that freedom. It was that conclusion which led the Constitutional Court to find that the prison authorities had the duty to strive towards a life sentenced prisoner’s rehabilitation and that rehabilitation was constitutionally required in any community that established human dignity as its centrepiece. Indeed, the Constitutional Court went on to make clear in the subsequent War Criminal case that this applied to all life prisoners, whatever the nature of their crimes, and that release only for those who were infirm or close to death was not sufficient (see paragraph 70 above).

Και, για να έχουμε και τον ποπό μας καλυμμένο, το δικαστήριο καταλήγει:

131. In reaching this conclusion the Court would note that, in the course of the present proceedings, the applicants have not sought to argue that, in their individual cases, there are no longer any legitimate penological grounds for their continued detention. The applicants have also accepted that, even if the requirements of punishment and deterrence were to be fulfilled, it would still be possible that they could continue to be detained on grounds of dangerousness. The finding of a violation in their cases cannot therefore be understood as giving them the prospect of imminent release.

Έτσι είναι. Όπως τα έχει πει 35 χρόνια τώρα το Γερμανικό Συνταγματικό:

Zu den Voraussetzungen eines menschenwürdigen Strafvollzugs gehört, daß dem zu lebenslanger Freiheitsstrafe Verurteilten grundsätzlich eine Chance verbleibt, je wieder der Freiheit teilhaftig zu werden. Die Möglichkeit der Begnadigung allein ist nicht ausreichend; vielmehr gebietet das Rechtsstaatsprinzip, die Voraussetzungen, unter denen die Vollstreckung einer lebenslangen Freiheitsstrafe ausgesetzt werden kann, und das dabei anzuwendende Verfahren gesetzlich zu regeln.

Προσωπικά δεν θα χρησιμοποιούσα επιχειρηματολογικά κατευθείαν την ανθρώπινη αξιοπρέπεια, αλλά θα αναφερόμουν μάλλον στον συνταγματικό πυρήνα της ελευθερίας ως φυσικής ελευθερίας: μπορεί να προσβληθή εν μέρει για πάντα ή πλήρως για λίγο, όχι όμως ολικά για πάντα.

Ακόμη και για τους δολοφόνους.