Slightly different version published in ekathimerini

Incidentally, the European Court of Justice just ruled that subsidies of almost 500 million euros given in 2008-2009 to the farmers by the Greek government, are illegal. They will now have to be paid back, who knows how.

The deepest harm inflicted on Greece by the EU, among the many benefits, is probably that it has maintained a large agricultural sector. Hundreds of thousands of young Greeks, instead of working hard in creative ways to gain a better future, just sit around waiting for European subsidies to materialize. Instead of utilizing their skills to create useful knowledge and innovation, they devote themselves to devising EU-fooling tricks and ways to block Greek roads.

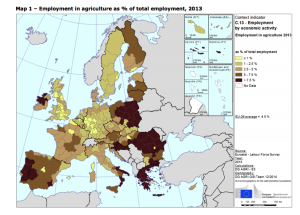

Notwithstanding what most Greeks think, the country is not truly agricultural – only about 13% of the population works in the sector. However, thanks to the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy, the Greek farming sector remains unusually big by European standards. Greece has the most farmers per capita after Romania, definitely more than the number that is needed or what the market would sustain.

The biggest issue with the farmers, is not that they regularly disrupt traffic and commerce on Greek roads, nor that they regularly support the most conservative currents in Greek politics. Farming in Greece is simply not contributing to the common good: they hardly pay any taxes (to finance the roads they are blockading for example), nor contribute properly to social security. And they do not contribute because they can not, they have no surplus of resources to share. This lack of resources is not manmade, but has to be attributed to nature: massive farming in Greece is doomed, clear as that.

Conventional wisdom within Greece and decades of development policy consider farming to be very useful. Many voices in the public debate argue that a return to farming might even be a solution to the Greek crisis. Both ideas are fundamentally wrong: Greece is not fit for modern massive farming and farming anyway cannot substantially contribute to GDP in a modern economy.

Consider the US as a modern economy, which incidentally also has the most productive farming sector. Well, in the aggregate US economy farming only contributes about 1% and no state (except for the Dakotas) has a farming contribution higher than 5%. In Greece, farming contributes about 3% of GDP, approximately 4 times less than its share of employment, meaning that farmers are about 75% less productive than the average worker!

Greek farming is so weak because farming, as any modern productive activity, requires economies of scale. Modern farms in Ohio or Florida use GPS guided driverless tractors, advanced irrigation systems with humidity sensors etc Today’s farmers are managers of big organizations, far from the suntanned sweating stereotype seen in novels. Farming in Greece is so backwards, not because of lack of human capital or access to the tractor market, but because of a lack of scale The average farm in Greece is 7 ha, versus 26 in Holland and almost 81 in Florida. Greek farmers are just too numerous compared to the efficiently farmable part of the land (which is way too small anyway, due to geographical factors). Expecting world class massive farming in Greece is like expecting one to build a BMW with a screwdriver and duct tape.

As a result, world agricultural prices which are formed in the American Midwest and the Argentinian pampa, are lower than the cost of Greek producers. The only reason for Greek to still exist is EU support in the form of duties on foreign food and mountainous subsidies splashed on European producers. For decades, one in two euros spent by the EU were not invested in education or research, or even consumed by welfare, but went to subsidize mountains of butter and rivers of wine!

What should be done now? Leave the farmers without gainful employment, run out of food and let the Greek countryside rot?

Not quite .

First, there might not be much to be done for older farmers, but there is no reason to raise new generations of them by distorting incentives. Why not give every young person considering farming a choice: run a farm or study at any university of your choice on the planet? Fuel subsidies for tractors, or funds for a start up? Give them freedom to choose, they’re not irrational, just victims of an irrational choice set inflicted on them.*

Now, what happens when young people stop farming, what do we eat? What every non-farming city dweller eats, Ohio corn, Ecuador bananas, whatever they want, cheaply and in unlimited quantities. The idea of agricultural autarky is not just economically silly, but just infeasible for most of the densely populated world.

So what about the natural landscape, won’t it degrade if farmers are not there to maintain it? On the contrary, farming is a particularly harmful activity. Where farms are now, forests used to be. Where millions of tons of water are spent now, creeks and rivers used to be. If we abandon the land that is of negative economic value for farming (removing the subsidies), we will have space for forests, parks, even urban expansion. In Greece’s case, there will be more space for tourist development too, which, per unit of income, is much more eco-friendly than farming.

Let’s make it clear: no modern country got rich because of agriculture, not even coutries with a long tradition of culinary marketing, such as France. Greek agriculture can, and will advance, focusing on small high-quality niches. But the Greek economy, or employment, will not advance based on farming. Let this ancient activity run its course into civilized retirement, a marginal sector for a few good men (and women) producing things they love. And let everyone else move on at last.

PS Many thanks to Saqib Jafarey for comments and suggestions.

*To the extent that the EU is unable to fundamentally reform the CAP, Greece could still, given its economic situation, try to ask for a shift in the CAP funds it is currently receiving, towards more productive aims, as listed above. Although it might be legally tricky, the EU and IMF would find it very hard to argue against such a move.

Εξαιρετικό άρθρο. Απορίες και σκέψεις:

1. Ποιο είναι το ποσοστό απασχόλησης στον πρωτογενή τομέα σε συγκρίσιμες χώρες, πχ Τσεχία, Πορτογαλία, Ιταλία; Ποια είναι η αναλογία απασχόλησης σε πρωτογενή προς ΑΕΠ πρωτογενούς;

2. Υπάρχουν κλάδοι της πρωτογενούς που ενδεικνύουν δυναμισμό και προοπτικές. Τα ψάρια υδατοκαλλιέργειας αποφέρουν εξαγωγικά γύρω στα 400 εκ. ευρώ ετησίως, κάπου εκεί και τα τυριά.

3. Ο τουρισμός και η γεωργοκτηνοτροφία συμβαδίζουν. Ο τουρίστας θέλει να φάη ντόπιο πράμα και όχι μακντόναλτς. Εκεί υπάρχει μέλλον.

4. Ένα άλφα ποσοστό πρωτογενούς υπάρχει και θα υπάρχη, για τον πολύ απλό λόγο ότι τα νωπά προϊόντα για να είναι νωπά μπορούν να παράγωνται μόνο τοπικά.

5. ΟΧΙ ΣΤΟ ΚΡΕΑΣ! ΚΑΤΩ ΤΑ ΑΜΝΟΕΡΙΦΙΑ! ΚΑΤΩ Η ΥΠΕΡΒΟΣΚΗΣΗ!

τα αμνοεριφια στα δινω ευκολα, τα γουρουνια οχι :)

4) βρε, αν ειναι υψηλης αξιας τα φερνεις (ή στελνεις) και με αεροπλανο. Πιο νωπα θα ειναι.

3) Αυτο μου ειπε και ο Σακιμπ

I must say I am very fond of Greek produce, I think it is superior to the much vaunted French one (I mean the stuff that comes out of the ground not what the bakers and chefs do to it) but I accept the wider economic argument.

Μονο που για τους Σακιμπ φτανει να παραμεινουν οι καλυτερες ελληνικες φαρμες, οχι και ολες οι αλλες που αργοπεθαινουν.

Παρεπιμπτοντως, με αυτα που λεω, μεσοπροθεσμα η παραγωγη δεν θα πεσει δραματικα πιστευω. Αλλα θα πεσει ο αριθμος των αγροτων, αυτο θελουμε!

2) Κτηνοτροφια κτλ δεν ειναι μεσα στα νουμερα. Φυσικα θεωρω οτι οι υδατοκαλλιεργειες ειναι χρησιμες (εχω φαει ελληνικο λαβρακι ακομα και στην Ουασιγκτων χαρη σαυτες), και πολυ υψηλοτερης αξιας.

1) Λειπουν οι συνδεσμοι, θα τους βαλω. Αλλα δες απλα τον χαρτη.

Πες μου και λιγο, πως διαολο θα επιστραφουν οι παρανομες επιδοτησεις?

4. Τα νωπά συχνότατα δεν μεταφέρονται εύκολα, βλ. ντομάτες, αβγά κλπ. Δεν είναι στην πράξη θέμα τιμής, δεν τίθεται τέτοιο θέμα.

Για τις επιδοτήσεις, δεν έχω ιδέα.

δεν μεταφερονται επειδη ειναι φτηνα. Αν ειχαν μεγαλη αξια, μεχρι και ενας πυργος φτιαγμενος απο τσοφλια αυγου μεταφερεται.

Ε ναι ρε, αυτό λέμε, στην πράξη δεν ποτέ δυνατόν προϊόντα που απαιτούν ελάχιστους πόρους, όπως οι φράουλες ας πούμε, να χτυπήσουν τέτοιες τιμές. Άρα, δεν μπορούμε να έχουμε εκεί τις εξαγωγικές ελπίδες μας.

http://www.waitrose.com/shop/DisplayProductFlyout?productId=45053

Origin:

Egypt, Spain(incl Canary & Balearic Is.), United Kingdom

Οι ντομάτες είναι συνήθως Ισπανικές, Ιταλικές και Ολλανδικές.

Βέβαια μιλάμε για προϊόντα χαμηλής προστιθέμενης αξίας που σε καμία περίπτωση δεν μπορούν να αντιπροσωπεύσουν μεγάλο ποσοστό του ΑΕΠ

Χαχα, πετάνε οι φράουλες; Μπράβο, Επ!